Kevin Stevens Conference

Hockey legend shares his struggle with drug addiction at Steele Hall

Kevin Stevens speaking during his Shattered Presentation in Steele Hall

October 28, 2022

A life of winning and losing, of championships and drug addiction, of feast and famine; Kevin Stevens said that the night he started doing drugs kicked off “just like any other night.”

From skating alongside (and almost outscoring) Mario Lemieux in the early 1990s to being arrested for drug crimes and losing millions of dollars in the years that followed, Stevens has seen the highest peak and the lowest valley.

It was a hockey-filled week at PennWest Cal, including the memorialization of deceased student and CALU hockey player, Branson King, as well as a memorial hockey game in his honor. Fans of the Pittsburgh Penguins on campus had an opportunity to listen to the stories of the 2-time Stanley Cup Champion Stevens, on Oct. 21 in Steele Hall.

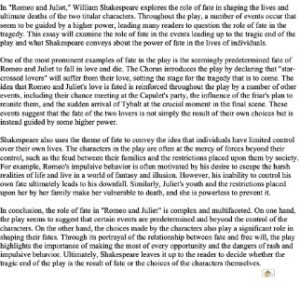

A sizable crowd filed neatly into Vulcan Theater as 7 p.m. drew near, and by the time the event started, there were hundreds of students from all walks of campus. They were all seated, silently reflecting on the multifaceted stories of one of hockey’s greats.

Previewing the crowd was the Emmy nominated Sportsnet documentary piece “Shattered”, which gave an overview of his troubles with addiction and sobriety. Stevens then took the stage to field questions about his life as an NHL pro, drug addict, and now-sober founder of the Power Forward Foundation, a nonprofit organization aimed at reducing the opioid crisis.

Questions flooded in from various spots around the auditorium, and Stevens had to pause multiple times to reflect on his past mistakes.

“The first thing I do every morning is wake up and admit that I’m an addict,” Stevens said. “I had the perfect life set up, and drugs interrupted that.”

Stevens, looking into the audience as if he’d given this narrative a million times, still showed emotion and concern for young people through his gruff New England accent, citing the recent epidemic of fentanyl-related drug overdoses.

“You can’t hide from it, you can’t run from it, because it’s all real,” Stevens said. “You people nowadays, you cannot make a mistake anymore. Is it worth making that choice?”

Stevens spent eight years with Pittsburgh skating with some of the best players in the world before he succumbed to drug addiction. When Stevens was traded away from the Penguins in 1995, he thought that a change of scenery would bring him some good fortune.

“I couldn’t perform like I used to because I was stuck in this thing,” Stevens said. “I thought being traded would bring a change, but I have to bring this brain with me.”

Sobriety was Stevens’s top concern following his arrest in 2016 for conspiracy to sell the commonly peddled pain medication Oxycodone. His journey through AA wasn’t easy, especially because, at first, he didn’t want to help himself.

“My friends wanted to help but they never knew what to do,” Stevens said. “The hardest thing to do is to help someone who doesn’t want to be helped.”

Now attending meetings three times per week, Stevens has remained in sobriety for over six years, and has re-established connections that he lost during his time in addiction.

“I did a lot of damage, and I hurt a lot of people,” Stevens said. “You don’t wanna look back, ya know? I just try to live where my feet are.”

Joshua Gutierrez, a Junior Marketing major, was in attendance for the event, and though a huge Penguins fan, Gutierrez wasn’t aware of just how famous Stevens really was.

“I’ve always admired those guys, those stars from the 90s Stanley Cup runs,” Gutierrez said. “I was very surprised to find out that he had such a key role.”

Stevens’s story of drug addiction hit particularly close to home for Gutierrez, who said that he, like many Americans, have family members who have died from overdose or laced narcotics.

“We like to think that it can’t happen to us,” Gutierrez said. “And yet, the stories keep coming in, and they’re becoming more common. The same people you might look up to watching your favorite sport can fall victim to it. Anybody you know can struggle with it.”

Gutierrez said that he agreed “absolutely” with Stevens’s statement that young people can no longer afford to make a mistake in today’s world.

“It’s not a mistake you can learn or grow from,” Gutierrez said. “You get one chance. Once that mistake is made, it can’t be undone. You just have to be careful.”

Kevin McTiernan • Dec 6, 2022 at 8:50 am

God bless and continue the fight and your rebirth. I loved watching you play on the wing and I’ll love to watch you win this battle.